Intro & Definition

The Pareto Principle, aka “the 80/20 rule”, aka “the rule of the vital few and trivial many” is the concept in which a small set of inputs to a function drive the majority of its output.

The principle highlights the fact that, when looking to improve the yield of a system, most of the time not all inputs are equally important. When this holds true, the best way to optimize is to find those highly influential inputs (“the vital few”) and focus heavily on controlling them. The rest of the inputs (“the trivial many”) don’t deserve nearly the love and attention.

Examples

- 10% of the people you work with cause 75% of the problems

- You use 5% of what you own 80% of the time

- You’ve already absorbed 80% of the value of this article, even though you’re only ~20% done reading it

Transfer Functions

Traditionally, the values associated with this principle are 80 & 20. These numbers are arbitrary, though. The rule could just as easily be the “90/20” or the “95/10” rule. The actual ratio depends on the shape of the curve drawn by the transfer function. Transfer function, in this context, is just a mathematical representation of the system in question. When you plot all possible outputs as a result of all possible inputs, that’s a transfer function. People like to keep things simple, and because terms like “transfer functions” are intimidating, we started calling it “the 80/20 rule”. The 80/20 rule is a simplified and easy to remember representation of a class of functions with asymmetric transfer curves. While not a universal principle, it is common in real-world applications.

The Law of Diminishing Returns

A special case of the Pareto Principle is The Law of Diminishing Returns. It is an economic concept which states that, as you continue to invest more resources into producing any particular good, you will tend to yield less marginal gain per unit of resource expended. Building a second factory may, indeed, double your output; but building a 20th factory won’t necessarily increase it at all. Buying a 2nd or 3rd pair of scissors for your house is handy, but nobody needs half a dozen pairs of scissors per room.

This is the Pareto Principle in action. Rather than the inputs being different from one another in their nature, they are identical inputs applied at a different time to a system that’s in a different state. In this case, 80% of the results gained from an effort may come from the first 20% of the resources you expend to get it. This links to the concept of Minimum Effective Dose, about which I may write more at some future date. It has all sorts of practical implications in life.

Positive and Negative Applications

The Pareto Principle can be exploited in many ways. You can use it positively, by looking for and doubling-down on those activities which bring you the greatest reward. You can use it negatively, by looking for and seeking to eliminate those activities which bring you the greatest costs/pain/dissatisfaction. Both approaches can yield high return on investment. Both are usually worth considering.

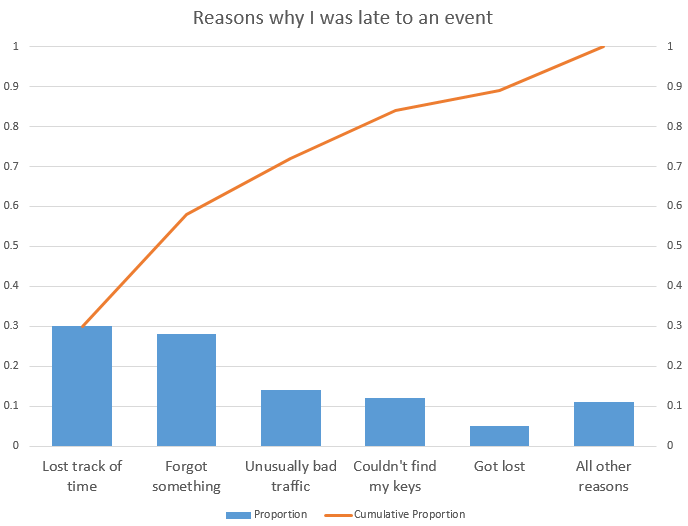

Example

Pareto Success Stories

Costco

Costco’s whole business model is an application of the Pareto Principle. Originally, Costco was like most other stores. If you wanted olive oil, you went to an aisle that had ~20ft of shelf space stocked with dozens of varieties of olive oil, despite the fact that 80% of the sales were coming from the 20% of the SKUs, that 20% were not getting 80% of the shelf space. Costco did away with everything that wasn’t a popular seller and doubled-down on those things that sold well. If you go to Costco looking for olive oil, you get maybe two choices… and because of the efficiencies they’ve gained from focusing in, your two choices are both good and relatively cheap.

Tim Ferriss

Tim Ferriss attributes a large part of his success to conscious application of the Pareto Principle. He describes how his business grew not by dealing with the 80% of the problems created by the 20% of the customers that created them, but instead by focusing on better serving the vital few customers who truly drove high volumes. Focusing on those customers gave him a better since of what a good customer wants and how to service their needs. This lead simultaneously to more high volume customers and fewer problems with which he had to deal.

Related Concepts

Minimalism

80% of your waking hours is spent with 5% of your possessions

Minimum Effective Dose/The Law of Diminishing Returns

Exercising for 3 hours does not yield three times the results of a 1 hour exercise

Literal Mathematical Functions

f(x, y) = 10x + 1y

Changing x yields 10 times the change of changing y

Sources

I utilized a few sources for this article.

- Tim Ferriss’s book “The 4 Hour Work Week” is essentially an extended manifesto of putting the 80/20 principle to work for you.

- Some Six Sigma training.

- Wikipedia. Yep.

- I vaguely recalled some stuff from a podcast from a while ago, but I don’t even remember the podcast.